- Home >

- Services >

- Access to Knowledge >

- Trend Monitor >

- Source of threat >

- Trend snippet: Hybrid threats are difficult to prevent through deterrence alone, different strategies are necessary

Trends in Security Information

The HSD Trendmonitor is designed to provide access to relevant content on various subjects in the safety and security domain, to identify relevant developments and to connect knowledge and organisations. The safety and security domain encompasses a vast number of subjects. Four relevant taxonomies (type of threat or opportunity, victim, source of threat and domain of application) have been constructed in order to visualize all of these subjects. The taxonomies and related category descriptions have been carefully composed according to other taxonomies, European and international standards and our own expertise.

In order to identify safety and security related trends, relevant reports and HSD news articles are continuously scanned, analysed and classified by hand according to the four taxonomies. This results in a wide array of observations, which we call ‘Trend Snippets’. Multiple Trend Snippets combined can provide insights into safety and security trends. The size of the circles shows the relative weight of the topic, the filters can be used to further select the most relevant content for you. If you have an addition, question or remark, drop us a line at info@securitydelta.nl.

visible on larger screens only

Please expand your browser window.

Or enjoy this interactive application on your desktop or laptop.

Hybrid threats are difficult to prevent through deterrence alone, different strategies are necessary

Scope of the framework

Many contemporary ideas on countering hybrid threats draw inspiration from a larger body of thought on deterrence. Hybrid threats are difficult to prevent through deterrence alone for an assortment of reasons. In a globally connected, multipolar security environment, technological developments have contributed to the democratization of the means of violence. This, at least in some cases, favors the offensive and renders deterrence unstable. Furthermore, by their very nature, hybrid actions are not always easily attributable which undermines deterrence. Some authors have also pointed to the overall declining payoffs associated with the manipulation of fear across a variety of domains which can be partially extrapolated to the security domain. Finally, our understanding of the role of psychology and perceptions has progressed to such a degree that it is necessary to broaden the framework to include influence strategies to dissuade but also persuade adversaries beyond deterrence alone. This brings us full circle back to insights already coined in the traditional deterrence.

literature which defines deterrence as “a process of influencing the enemy's intentions, whatever the circumstances, violent or non-violent.”

The framework’s two axes

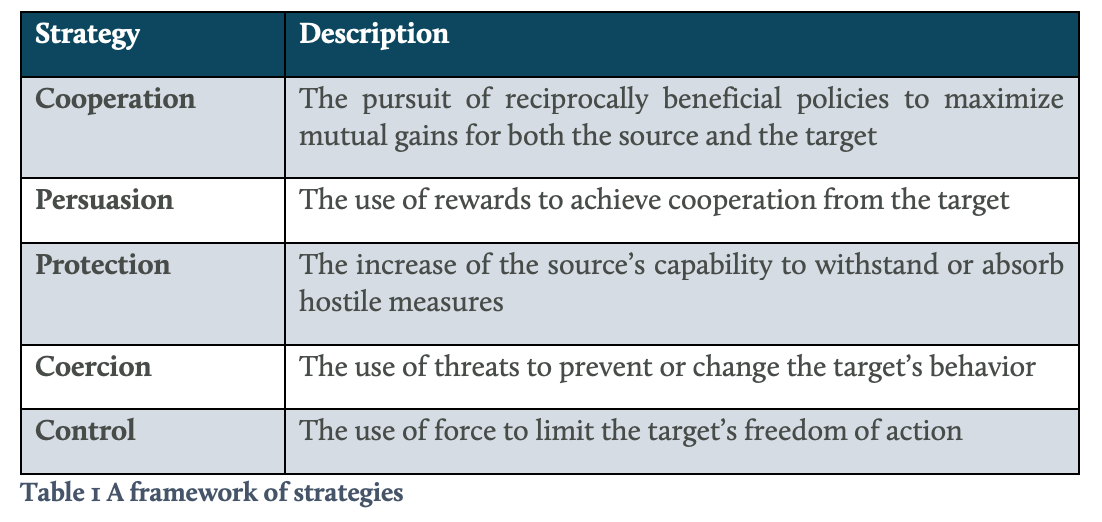

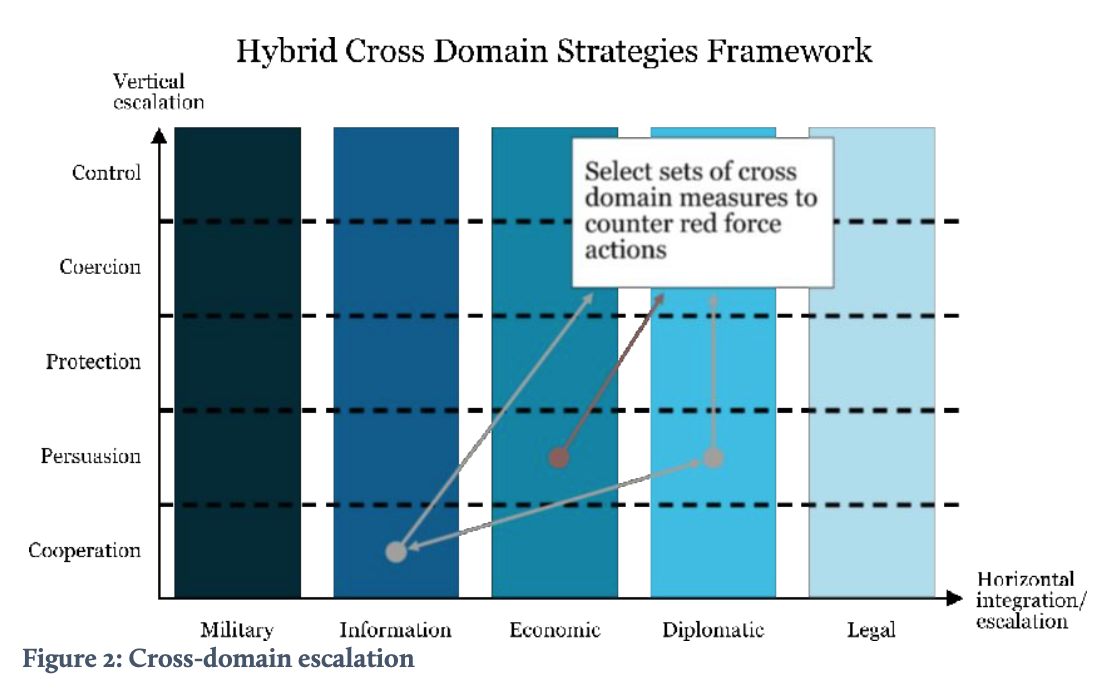

In recognition of the above, our framework consists of two axes to differentiate between the range of strategies that can be applied against hybrid threat actors. The combination of the two axes gives a full conceptual range of types of strategies to apply in a hybrid threat context. Our framework explicitly draws on and extends the survey of King Mallory on different strategies in his analysis of cross domain deterrence from 2018.2 Vertical (de-)escalation options The vertical axis consists of five general strategies: cooperation, persuasion, protection, coercion, and control (see Table 1). These five strategies differ in the appliance of sticks or carrots in order to influence the behavior of the other party, as explained below.

Cooperation is the pursuit of reciprocally beneficial policies to maximize mutual gains for both the source and the target through entanglement, conciliation and accommodation.3 Entanglement typically takes the form of creating mutual dependencies, usually economic or supply-chain based, whose disruption would reciprocally harm both actors and thus disincentivize destabilizing actions. Conciliation refers to removing key obstacles to reaching an agreement, without agreeing to a major part of the other side’s demands. This mode of negotiation seeks a win-win solution rather than win-lose or zero-sum distributive bargaining. Accommodation involves minor concessions from one side (although they may be communicated as substantial concessions to the target) to achieve agreement. The crucial caveat is that cooperation requires reciprocal good faith. Absent that, the other party can exploit a cooperative strategy to achieve its own objectives or revert to confrontational distributive bargaining. Cooperation can enhance protective and persuasive strategies. It may stack with coercion but is unlikely to work well alongside control. Persuasion uses rewards to achieve cooperation from the target, as an alternative for continued confrontation. It requires some goodwill on the part of the target; and thus a pause or reversal of escalatory actions, as well as effective communication to convey overtures by which a target can reciprocate without being seen to lose legitimacy or capitulate. Successful persuasion leads to win-gain scenarios. Material forms of persuasion include economic inducements or other tangible rewards. Immaterial forms include the prospects of status, prestige, good relations or credible reassurances about the other’s security. Persuasion may be combined with some form of coercion or of cooperation. Persuasion does not work well alongside control strategies because it loses much of its credibility when unilateral violence is introduced into the equation. Protection aims to increase of the source’s capability to withstand or absorb hostile measures and typically results in win–zero scenarios. The two basic forms of protection are resilience and defense. The function of defense is to thwart attacks, while the function of resilience is to mitigate its consequences. Both resilience and defense can be conducted across all sectors and domains. The main purpose of both is to deal with the actual hostile measures. Yet, ifthey are strong, they can also help to dissuade a target from carrying out hostile measures because the target will not yield expected benefits. This gives protective strategies the potential to enhance deterrence methods. For all these reasons, both forms of protection need to be constantly updated to keep pace with the most recent character of the threat. Coercion, in contrast to the reward-centric cooperation and persuasion, conveys persuasion to adversaries via negative means. It compels another actor to do something it does not want to do through deterrence and compellence. The former entails the use of threats to dissuade the target from taking a particular action, the latter to convince the target to take a particular action. Successful coercion typically results in win-lose scenarios. Examples span the range of sanctions regimes, bilateral diplomacy, and the use of cyber and hybrid tools, as the use of explicit military tools of coercion has been reduced by (most) actors in modern times. Coercive strategies can also be conducted by threats of shaming or stigmatization. Unlike protective strategies, coercive strategies target specific adversaries for specific ends. This implies that threats need to be tailored to the character of the target and the intended change of behavior. Therefore, the conduct of coercive efforts needs to be rooted in a clear understanding of one’s vulnerabilities and of the character of the hostile measures, as well as a detailed understanding of the desired change in behavior one wishes to induce. Failure to do so may lead to miscommunication, provocation and escalation. Control refers to the use of force to limit the target’s freedom of action. . Successful control typically leads to win-defeat scenarios. Control strategies involve prevention or preemption. The former uses active measures that degrade the target’s capability to pose a threat before it has become imminent; the latter forcefully eliminatesimmediate threats. Both are aimed at specific adversaries. The major risk of control is that it may increase rather than decrease the target’s willingness to implement hostile measures in response to an attack. In other words, control may as much provoke attacks as it can prevent them. These five strategies can be used simultaneously or sequentially. In both cases, strategies should be used carefully to rectify each other’s deficiencies and to enhance their potential. Some strategies, such as cooperation and protection, always amplify each other’s potential. Other strategies, such as control and persuasion will undermine each other if used in tandem. All strategies contain some limitations and risk of failures and therefore no single element may constitute a singular means of ensuring security.

The five strategies can be plotted on an escalation ladder, a spectrum from the least escalatory to most escalatory measures (see Figure 1). Escalation refers to an increase in the intensity or scope of conflict that crosses the threshold(s) considered significant by one or more of the participants. The escalation ladder represents a metaphor in crisis management in which actors can take steps to manage the intensity of the conflict, either through the escalation, de-escalation or a combination of the two via different channels in order to communicate with an adversary. All strategies can be used for both escalatory and de-escalatory purposes except cooperation, which by definition leads to de-escalation. This also implies that strategies should be employed carefully to augment each other’s (de)escalatory potential rather than hinder, or in the case of using control and persuasion strategies simultaneously, undermine each other. If one seeks escalation, then it does not make sense to use cooperation alongside coercion and vice versa. The common denominator between strategies must be recognized in their utilization across domains.

Horizontal (de-)escalation options

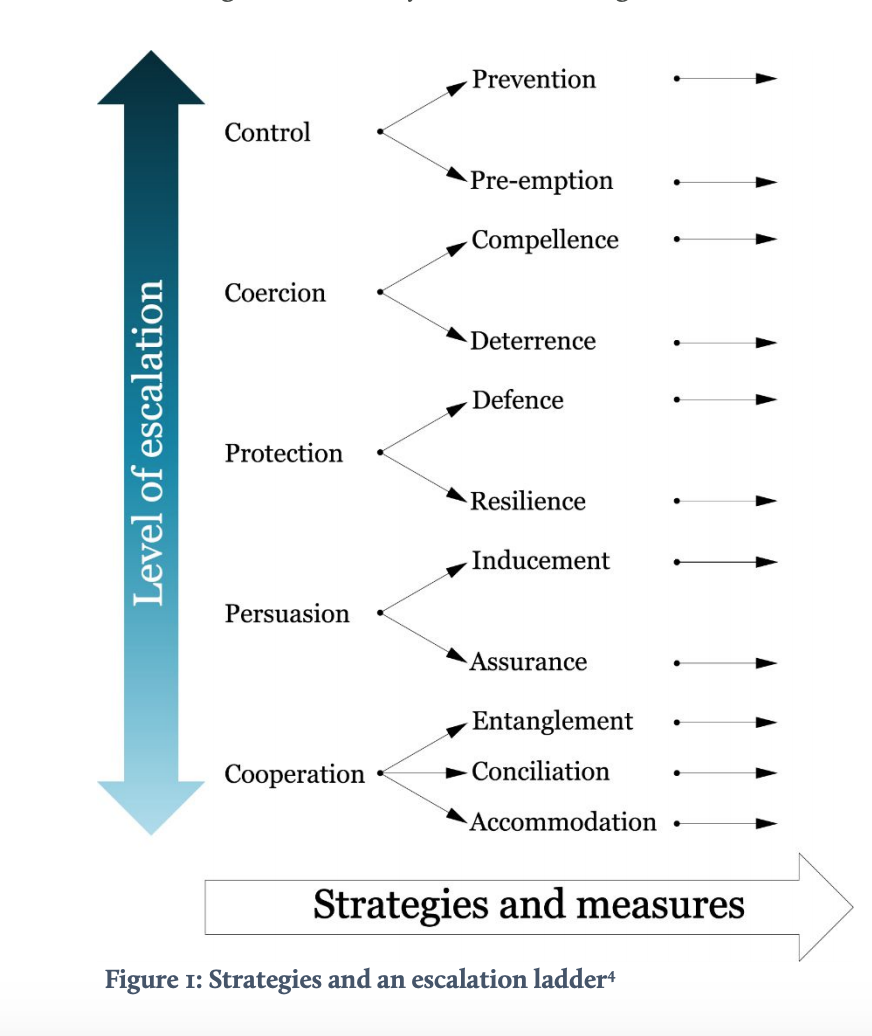

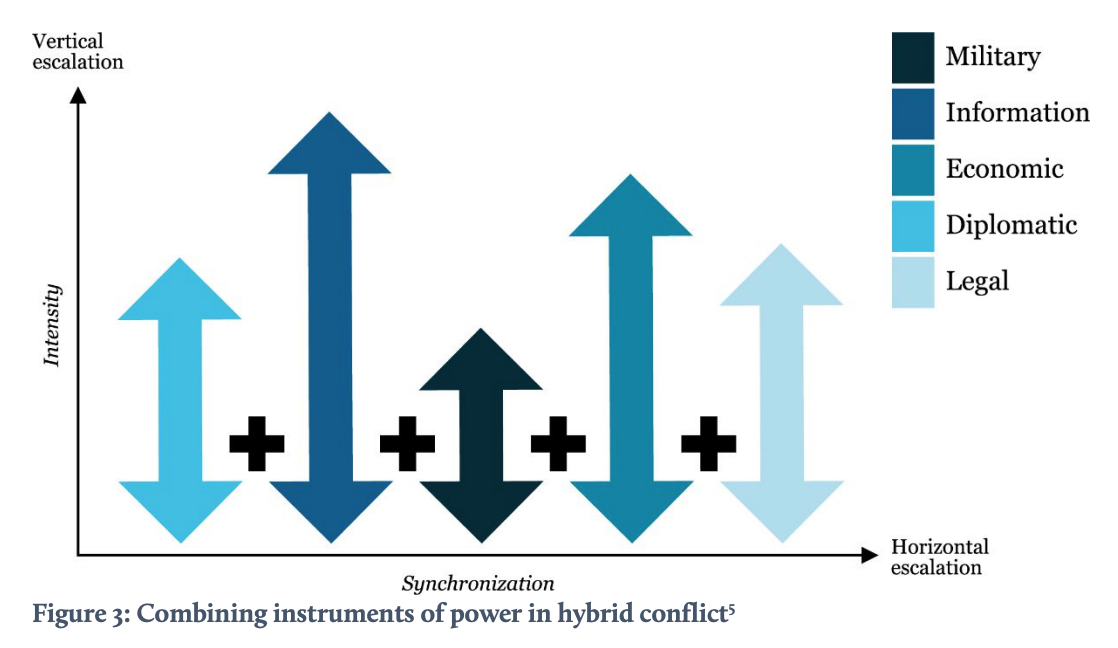

In addition to vertical (de-)escalation options, one can also escalate horizontally (see Figure 2). For this, the framework uses the well-known DIMEL categorization of instruments and measures of state power, distinguishing between Diplomatic, Information, Military, Economic, and Legal domains. Vertical measures convey escalation within the same domain. For example, if hostile measures revolve around cyber espionage, a vertically escalating response may include acts of cyber sabotage. In contrast, horizontal escalation refers to broadening the scope of efforts beyond a single DIMEL domain to other domains. For instance, diplomatic and economic sanctions can be used in response to military aggression, as the West did in the aftermath of the Russian annexation of Crimea. One level deeper, horizontal escalation can also take place within various military domains. Israel, for instance, used airstrikes against Hamas in the spring of 2019 in retaliation for a series of cyberattacks, utilizing a kinetic countermeasure to a cyber threat.

In hybrid conflicts, actors not only switch between domains but also combine the different power instruments while varying the level of intensity per domain (see Figure 7). By doing so, hybrid actors typically move up and down the escalation ladder in what is called the grey zone between war and peace, while avoiding the threshold that would lead to open (military) conflict. In addition, hybrid tactics leverage conventional and attributable actions to reinforce non-attributable efforts, and vice versa. Sometimes the aim is to achieve military and political objectives fast, presenting a fait accompli – an outcome already accomplished and presumably irreversible – before an allied response can prevent it. Note that the intrinsic ambiguity of this ‘hybrid’ use of measures may cause a (dangerous) divergence in perception between the source and the target on what constitutes an escalatory or de-escalatory step.

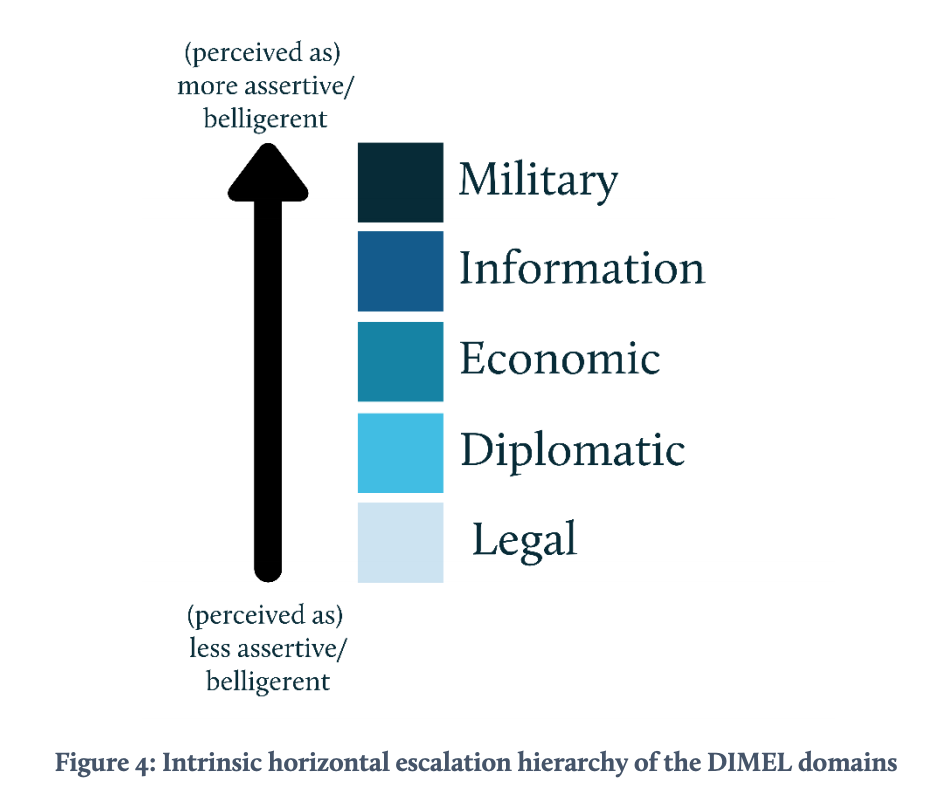

In principle, the escalation ladder from Figure 1 is generic in the sense that it may be applied to all DIMEL domains. However, the various levels have quite different annotations for the distinct domains and might be more applicable in some combinations than in others. Indeed, a particular low level action in one domain can have more impact than a high level action in another domain. Further note that, next to this vertical escalation ladder, moving from one DIMEL domain to another in itself may be perceived as an (horizontal) escalation step by the target, even if the initiator did not intend to escalate. In other words, the levels of escalation have no absolute value across the various instruments of power and influence. (Figure 4 depicts a nominal horizontal escalation hierarchy.)

From Single Domain to Cross-Domain Strategies: Issues to Consider

The cross-domain character of contemporary conflict adds another layer of complexity to the portfolio of strategic options, namely the multiplicity of instruments through which the strategic efforts can be conducted. To provide guidance on how to think about the salient issues in the selection and execution of cross-domain strategies in hybrid conflicts, we have delineated five kinds of assessment that need to be conducted before, during, and after the employment of strategies in the cross-domain context.

Cost-Benefit Assessment. This type of assessment presupposes prior selection and prioritization of objectives. It is relevant to start with the assessment of benefits because these should be directly related to the objectives that are pursued. The bottom line is that no matter how great the benefits are, if they do not contribute to the relevant objectives then the strategy may be either irrelevant or outright damaging. The calculation of benefits in the cross-domain context needs to consider the potential interaction between instruments, which may enhance or degrade each other’s effects. For example, the potential benefits of controlling strategies are likely to be enhanced when conducted across military, diplomatic and economic domains, because in all these forms the strategies drain away from the adversary’s resources. On the other hand, coercive strategies conducted across domains may not enhance each other’s potential because the adversary is likely to pay attention to the most dangerous threats and to ignore or neglect the rest of them. A similar logic applies to the assessment of costs in the cross-domain context. Controlling strategies exercised across military and economic domains are always bound to be expensive while those relying on the use of diplomacy and information may be cheaper. The cost-benefit assessment should also consider the potential costs associated with risks attached to a particular course of action and its failure.

Cross-Domain Orchestration Assessment. Strategy needs to be implemented in practice. The cross-domain context allows for a broad spectrum of options to choose from. For small and middle powers, the international context and the position of allies and friendly nations will need to be considered since actions are typically conducted within the context of international coalitions. It is then crucial to know the priorities and means available to others because these determine the character and the extent of effort allies are willing to invest on their own behalf. Cross-domain orchestration at both the international and the national level brings with it an assortment of additional challenges. It is necessary to know who is responsible for the mobilization, coordination and employment of the diplomatic, information, cyber, economic, military and legal instruments as well as which actors possess the mandate to employ these resourcesto pursue objectives in unlike domains. The complexity of orchestrating cross-domain instruments are further exacerbated by the fact that responsibilities and capabilities are spread out over different government departments. It is therefore necessary to identify the mandate and the responsibilities for the use of resources in addition to the coordination mechanisms for how these means can be used.

Proportionality Assessment. The appraisal of the cross-domain strategy’s proportionality in relation to the particular challenge at hand requires an assessment of that challenge. Proportionality is then a subjective metric but it is generally a function of two distinct sources – instruments and effects. Proportionality of instruments relates to the character of the domains in and through which the strategy is employed. A basic level of proportionality can be achieved by using military instruments to counter military threats and non-military instruments to counter nonmilitary threats. It also follows that, in general, using the military instrument to counter non-military threats is likely to be disproportional. The proportionality of effects is more complicated because the latter cannot be easily categorized and, therefore, contrasted. Nonetheless, it is possible to divide effects into physical and psychological ones. Physical effects are more proportional to other physical effects while psychological effects are more proportional to psychological effects. At the same time, it is necessary to acknowledge that in the cross-domain context most instruments, most of the time, produce both physical and psychological effects. It is therefore necessary not only to assess the character of the effects but also their severity. For example, while military and economic control both produce physical effects, the former tends to be more severe than the latter, particularly in the short run. These points tie back to the escalation ladder introduced earlier, which is essential to navigate potential escalation dynamics during the conflict.

Signaling Assessment. This type of assessment pertains to the anticipation of how the adversary, as well as domestic and international audiences, are likely to perceive the actions and what psychological effects will be produced by strategic signaling. The execution of every strategy signals a message, whether that message is intended or not. The psychological effects of signaling largely depend on the cognitive processes of the respective audience and on the escalation potential of particular domains. For this reason, it is necessary to have some level of understanding of the particular belief systems and perceptions of the relevant audiences. At the same time, it is also crucial to understand that strategies conducted in and through some domains may appear less escalatory than those conducted in other domains. Signaling will be more complicated in some domains than in others. The solution to the signaling puzzle resides in the right combination of instruments so that these enhance each other’s signaling potential. For example, coercion exercised through cyber instruments could be complemented by economic or military instruments so that the adversary is less likely to misunderstand or ignore the message. In sum, the assessment of effects produced by strategic signaling rooted in a good understanding of an opponents’ belief system sheds light on the potential conversion rate between the use of strategies and the psychological consequences they are likely to create.

Legal and Normative Frameworks Assessment. Here the first question is whether the domestic legal framework allows for the selection of the strategy but also whether it allows for the prolonged exercise of the strategy. It is necessary to assess which options are legal in particular domains but also across them. For example, some legal frameworks may only allow for offensive cyberattacks to target military rather than civilian infrastructure. The second question is concerned with the legitimacy of the strategy from the perspective of both international law and international norms. Additionally, it is also important to assess whether the conduct of particular strategy conveys the emergence or propagation of a new norm of behavior or whether it falls within the framework of the existing norms.